CZECH EMBASSY IN ADDIS ABABA

__________

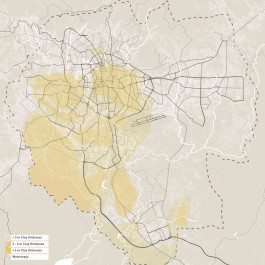

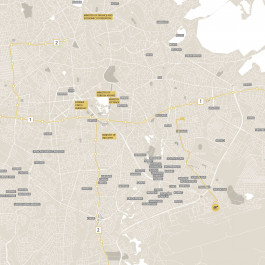

Ethiopia and especially Addis Ababa are places of great change. Rapid urbanisation makes Addis Ababa one of the fastest growing cities on the planet, tenfolding its population since 1950. But at the same time building materials are scarce, almost everything from concrete to steel has to be importet. Ethiopias forests have been cut down by around 70% in the last century and people are desperately trying to save the remains.

All these factors make contruction by standard western means – e.g. reinforced concrete structures with chemical insulation - unsuitable, expensive and ecologically problematic. But still, almost all of the current building projects in Addis Abeba are build in that way.

The potential architectural answer to these problems is deeply rooted in Ethiopian culture and far from innovative: earth. Rammed earth contruction is essential to Ethiopias rural architecture, but therefor known as a material for the poor. It is seen as a material of lesser worth and its bad reputation might be the reason for its decline in Addis Abebas urban architecture.

But local experts like Helawi Sewnet and Zegeye Cherenet are campaining for a new, sustainable and affortable building practice in Ethiopia, centered around earth as its main material. Numerous projects and publications by people like Martin Rauch and ZRS Architekten proove, that rammed earth can be used extensively for the demands and applications of a modern building. Its outstanding climatic qualities and its capability to bear loads allow for monolithic contruction which is not only elegant but also quick to build and cost effective.

This design for the Czech Embassy in Addis Ababa tries to ressurect the traditional Ethiopian material earth, by celebrating it in a building of highest representation and by combining it with the clear and careful shapes of Czech modernism.

Project description

The typology of an embassy is particulary unique. Inherently different and sometimes conflicting functions have to be combined into one structure. This structure does not only serve representative functions but also has to provide a comfort for visitors, employees and especially inhabitants, all while retaining a high standard of security and complexity. The biggest conflict, which is unusual even for an embassy, is the fact that the czech employees will live and work on the site. They will expect a difference in typology between the place they work and represent the czech republic and the place they live with their families. This contrast will have to exist architecturally, but the structure as a whole has to remain as one, both visually and functionally.

Spatial Articulation through Wall Typologies

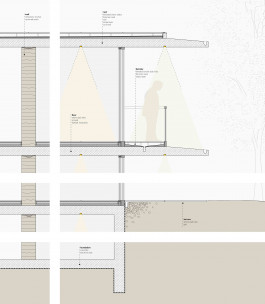

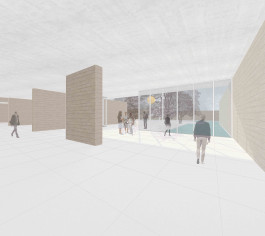

The wall serves as the central design element—not merely as enclosure, but as a spatial, structural, and atmospheric device. Referencing the tradition of the freestanding wall in Czech modernism, three distinct wall types define the architectural composition: rammed earth, glass, and corten steel.

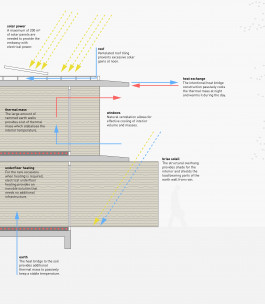

The rammed earth wall functions as the primary load-bearing structure and spatial divider. It encloses the site, defines building volumes, and organizes both interior and exterior zones. Its thermal mass provides climatic buffering, while its extension into the landscape creates nuanced transitions between public, semi-public, and private realms.

The glass facade takes advantage of Addis Ababa’s temperate climate to dissolve boundaries. Large operable openings allow for fluid continuity between interior and exterior, expanding representative and domestic spaces beyond their physical limits and generating a sense of openness within a dense context.

Corten steel panels complement the glazing by offering visual privacy without sacrificing natural light. Laser-cut with a pattern inspired by traditional Bohemian glass cutting, they introduce a crafted ornamental quality while referencing the natural texture of the rammed earth.

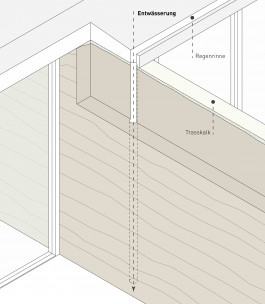

All wall types are unified by a freely spanning concrete slab that forms both interior and exterior spaces. Its generous overhang provides shelter from intense sun and seasonal rains, reinforcing the project’s horizontal layering.

Spatial Strategy

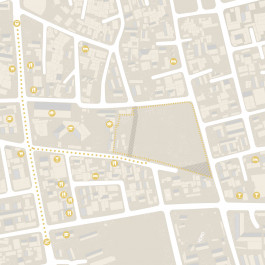

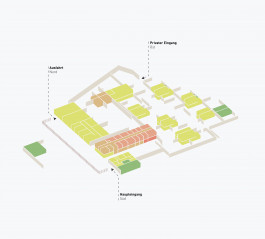

The site is divided into a representative western zone and a private residential eastern zone. A forecourt along a new western access road stages the embassy’s façade. Opposite, a staff building continues the architectural language and frames the entrance sequence.

Programmatic Hierarchy

Representative functions are arranged around a central garden, with large openings creating continuity between interior and exterior. The ambassador’s residence bridges public and private realms, ensuring functional independence with spatial coherence.

Security and Zoning

Office volumes shield the garden to the south; secure areas are inward-facing and clad in corten panels. Technical infrastructure is concentrated in the basement. The consulate, directly on the street, acts as a public interface and additional security layer.

Topography and Separation

A 1.9 m level drop and rammed earth walls separate the residential area, connected only via the office wing and the residence. The northern garden of the residence allows for informal or private use.

Residential Ensemble

Staff housing forms a compact, village-like structure within a tessellated garden. Fragmented volumes, private terraces, and communal outdoor areas promote autonomy and a clear distinction from the workplace.

University:

Studio:

Project:

Support:

Students:

Semester:

Staatliche Akademie der

Bildenden Künste Stuttgart

Free Project

Bachelor Thesis

Czech Embassy in Addis Ababa

Prof. Fabienne Hoelzel

Prof. Matthias Rudolph

Markus Schiemann I Jasper Eck

SS 2019 Bachelor